The Gazette is working with the Linn Landowner Forum to present a weekly series of columns about elements landowners should consider when replacing trees and plants lost in the Aug. 10 derecho. The series will focus on recovery, the importance of native plants and other topics. Sixth in a series and is written by Kent Rector.

Kent Rector is the nature center manager for Linn County Conservation, where he develops hands-on, experience-based learning opportunities for students and oversees the Wickiup Hill Learning Center. Kent and his family recently moved to Mount Vernon from southeast Iowa. (Supplied photo)

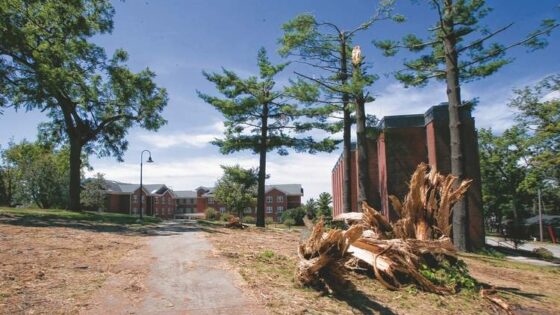

Like it is with most of you, the Aug. 10 derecho still is a very vivid memory for me.

I rode the storm out in my pickup truck, parked along Highway 13. It wasn’t until after the wind had passed that I realized just how severe the storm was.

But this column isn’t about the damage and destruction caused by the storm. It’s about the change that is following it, or more specifically, the change it is bringing to my yard and how I view urban landscapes.

My family and I moved to the area about three weeks before the derecho hit. At our previous home, we had a garden, kept bees and chickens and had several fruit trees, as well as perennials, to harvest from each year.

Subsidizing our meals with food grown on-site or gathered locally has become part of our identity as a family.

We enjoy the entire process of planning, planting, harvesting, preparing and preserving. There is just something comforting and rewarding about a meal into which you’ve invested time and energy.

We feel a connection and kinship to the land and by gardening: We believe we are not only improving our personal health, but the biodiversity and health of the landscape as well.

So being new to the home and urban lifestyle, we were already talking about changing the cookie-cutter landscaping around our lot into something more alive; the storm just helped to expedite the process.

Did you know that turf grass is the No. 1 irrigated crop in the United States?

According to a 2002 U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture report, turf grass was estimated at 50 million acres in the United States, making it the fourth-largest crop overall and the largest irrigated crop in the nation at that time. And that represents only sod grown commercially.

A 2015 study conducted by NASA estimated that turf grass or lawns take up three times as much area as corn.

These familiar patches of green littering our urban landscapes can consume 9 billion gallons of water a day, not to mention the 90 million pounds of fertilizers and 75 million pounds of pesticides applied by homeowners annually.

All that for a crop we can’t eat and that has little, if any, ecological benefit.

There are two positives to turf grass that I should mention — carbon trapping and erosion prevention — but when you really dig into it, what are we getting from all that green grass?

Creating a more efficient, self-sustaining and edible landscape, especially in town, not only makes sense to me, it’s kind of trendy right now.

For more than a decade, “unlawning” — or the act of turning lawns into fertile, edible landscapes — has been gaining popularity in the United States.

A view of Kent’s former garden in southeast Iowa. (Supplied photo)

These edible yards aren’t just backyard garden plots with a few squash and tomato plants. Rather they are landscapes that incorporate edible native plants, like pawpaw trees or serviceberries, along with fruit trees, pollinator habitats, medicinal herbs and water features.

In fact, we have a really good “unlawning” resource right here in our backyard.

Iowa City-based Backyard Abundance is an edible landscaping organization created in 2006 to help people create beautiful, environmentally beneficial landscapes that provide healthy food and habitat. The organization has loads of resources and provides classes for anyone interested in learning more about unlawning.

There are also many books and online resources, such as “The Tenth Acre Farm,” which is a blog dedicated to “permaculture for the suburbs” that provides more than 10 years of edible lawn tips and tricks.

Creating an edible landscape is a fulfilling project. Start this winter by observing your areas. Draw a map. Make a list of plants you are interested in; I suggest sticking with perennials. Take note of any needs, such as privacy or high traffic areas. Research different ideas and techniques, then make a plan. You will ultimately increase your yard’s productivity, biodiversity and aesthetic appeal.

In the aftermath of the storm, you have a brilliant opportunity to revise your yard into something more.

Plant the seeds that will ultimately help nature, grow food and protect pollinators. Let your yard enrich your life and not just become another space to mow.

Terra Rector, daughter of Kent Rector, stands under a bean trellis in the family garden. Kent Rector is the nature center manager for Linn County Conservation, where he develops hands-on, experience-based learning opportunities for students and oversees the Wickiup Hill Learning Center. (Supplied photo)

Take this opportunity to create new spaces and memories. In the end, you may end up growing a bit as well.

Kent Rector is the nature center manager for Linn County Conservation, where he develops hands-on, experience-based learning opportunities for students and oversees the Wickiup Hill Learning Center. Kent and his family recently moved to Mount Vernon from southeast Iowa. They love to get outside, explore new areas and garden.